In the post I'd referenced above, Liftig dressed up as Abramovic, down to the single braid falling over her shoulder and proceeded to mirror her, sitting across from her motionlessly for the entire day, leaving only when the guard's ushered her out at the museum's closing. She labeled her corps-à-corps with Abramovic "The Anxiety of Influence," after Harold Bloom's famous study and theory. I was curious to see if someone else would try Liftig's approach while I was at the museum, but no such luck. Nevertheless, when I arrived at the exhibit, amidst a large crowd drawn not only by the Abramovic show but by concurrent shows focusing on Tim Burton (sold out), Picasso (a crowd pleasure), and William Kentridge (which I also viewed), a young woman was sitting facing Abramovic intently, almost as if throwing down the gantlet, and I watched Abramovic and her for a while, trying to register any response on Abramovic's part while also trying to discern the ferocity I perceived on the young woman's face, in her posture, in her affect. It was almost as if she were viewing the performance as a form of mild combat, and her rigidity and stillness did not ebb in the slightest for the entire time that I watched them; Abramovic, for her part, slumped a bit forward, moving only her eyes, present in body and mind, a presence writing herself into the consciousness of everyone there. I was, almost in spite of myself, riveted by them.

There wasn't a long line, so I could have gotten in it and possibly faced Abramovic, but I wasn't sure I was ready to do so--if you do face her, you consent to being both photographed and filmed by the museum and her--and I wanted to see the rest of her exhibit, on the 6th floor, so I asked the guard how long the young woman had been sitting there, and he told me with weariness that she'd been there for about 20 minutes. I'd taken a few photos, which were verboten, and the guard saw me about to take yet another and stopped me, so I showed him that I could draw on the phone, and he carefully watched me for a while as I did a quick sketch of Abramovic, which I posted below, then headed upstairs. It was definitely worth it.

There wasn't a long line, so I could have gotten in it and possibly faced Abramovic, but I wasn't sure I was ready to do so--if you do face her, you consent to being both photographed and filmed by the museum and her--and I wanted to see the rest of her exhibit, on the 6th floor, so I asked the guard how long the young woman had been sitting there, and he told me with weariness that she'd been there for about 20 minutes. I'd taken a few photos, which were verboten, and the guard saw me about to take yet another and stopped me, so I showed him that I could draw on the phone, and he carefully watched me for a while as I did a quick sketch of Abramovic, which I posted below, then headed upstairs. It was definitely worth it.While the nude performances unsurprisingly have drawn a lot of attention and sparked some misbehavior on patrons' part (when are most people, especially men in this society, socialized to act maturely around nudity, especially nudes of the opposite sex, except perhaps in a locker room?) and are eye-catching at the very least, what I found even more compelling was the historical trajectory of Abramovic's solo body-centered performances, with a fused personal-political edge, in 1970s Belgrade. The earliest series, called "Rhythm," culminated in Rhythm 0, reminiscent in some ways of Yoko Ono's Cut Away and similar Fluxus actions of the 1960s: taking "full responsibility" for her passivity, she stocked the gallery with 72 items, including knives, a hammer, a saw, a pistol and bullet, a whip, blue paint, and so forth (I actually wrote down all the materials listed), and empowered the audience to utilize any of these implements on her. While it appears several men did undress her or adorn her with paint, one, horrifyingly, loaded the bullet into the pistol, placed the gun in Abramovic's hand and then lifted it to her head, before setting it back down. I read this in part as a demonstration of the humanity and rationality underlying the alternately liberal and brutal political, economic and social system in which she was living, as well as a commentary on social and gendered power, participatory art and chance, but also as a kind of limit test for the sort of conceptual, aleatory and performance art that she had been engaged in up to this point. When I think contemporary public discourse in the US, I shudder to consider an artist attempting this today.

The show then shifted to her later projects with her partner at the time, Ulay (Uwe Lay Siepen, 1943-), with whom she performed some of her most famous pieces, including early versions of what would become "The Artist Is Present." Some performances involved extending ideas to their logical or illogical end, as when the two stood back to back between two pillars and rush forward until they banged into the barriers, then walked backwards, or a durational performance in which the two screamed at each other, or sucked breaths from each other, or slapped each other; in all cases, both Abramovic's and Ulay's bodies served as the ground and primary medium of art, and again, the personal and public fused, as they had a relationship during this period that lasted until around 1988, when they embarked on their final joint performance, approaching each other from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China, and then formally bidding each other goodbye when they met at the midpoint.

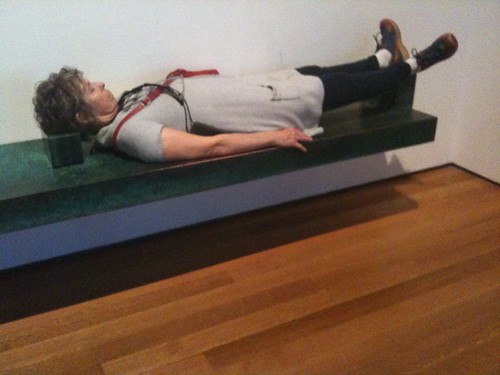

After this Abramovic returned to solo performances, but also has staged events involved others, created sculptures, made videos, and continued along the path she marked out in her early work, though since the fall of the Berlin Wall and subsequently of Yugoslavia, the political valence has shifted, I'd, towards a critique of the personal itself and of the myth, practices and possibilities of conceptual and performance art. One of her most famous US events occurred in November 2005, when over the span of a week she staged Seven Easy Pieces, a re-enactment of seven noteworthy performance pieces, by artists such as Bruce Nauman (Body Pressure, 1974), Vito Acconci (Seedbed, 1972), Valie Export (Action Pants: Genital Panic, 1969), Gina Pane (1973), Joseph Beuys (How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, 1965), and herself (Lips of Thomas, 1975), from the heyday of conceptual and performance art, on and beneath a large round stage, at the Guggenheim Museum. (I remember when this piece was performed, but I was in Chicago and didn't get to see it.) To these she added one new piece, Entering the Other Side, 2005. The Lips of Thomas was and remains particularly notorious because it involved Abramovic not only carving the Yugoslavian star into her stomach with a razor blade, but then lying on a bed of ice, while a heatlamp increased blood flow from her open wound. At the initial performance, audiene members pulled the ice blocks from beneath her, but, from what I gather, did not do so in New York. The 6th floor exhibit documented all these performances in depth, and includes several reenactments of individual and duo pieces. These include the nude human walkway--which I did pass through, rather clumsily--and the woman on a bike seat, though unlike in Abramovic's earlier version, these performers were suspended high above the audience. The woman who was performing it when I initially entered the room seemed almost to be tearing up; after noticing this, and her intent gaze back at an elderly man who appeared to be transfixed by her, I had to walk away. Yet another piece, originally performed by Abramovic and now enacted by someone else, involved the woman lying nude beneath a human skeleton, her breathing animating it. As I stood watching her, a man was taking pictures (forbidden), and she looked back intensely, though eventually a guard did tell him to stop. With both these nudes, the power dynamics I saw on display disturbed me a bit, and I wondered if I would have felt the same way had men been perched nude up on the wall or lying beneath the skeleton. (Perhaps they were; I missed them.) Before I left, I made a point of taking part in at least one more interactive piece, Abramovic's wall sculpture, The Green Dragon Lying (1989), a slab of marble and a quartz pillow spectators are invited to lie on, until they feel the spiritual effects Abramovic suggests the piece conveys. I lay on it for about 2 minutes, as a large crowd gathered in front of the video of Lips of Thomas, which featured Abramovic flogging herself, and rested there for a while. I thought I perceived someone photographing me, so perhaps a photo of yours truly is now part of someone's archive.

Before I left, I passed through the William Kentridge exhibit, but I was almost too exhausted--in a good way--by Abramovic's tableaux (some vivants) and documentation to really imbibe Kentridge's compellingly complex artworks. I did study some of the mixed media paintings, drawings, prints, and etchings, though, and was able to appreciate in a way that no photograph of his work can convey the layers of material and media constituting each. I read this layering, its richness and invisibility except upon close viewing, and his restrained color palate (mostly blacks, whites and grays) as obvious but productive metaphors for the longstanding realities of his native country, South Africa. I would like to go back and see his exhibit again before it closes. Below are some photos I took of the 2nd floor performance.

"The Artist Is Present" from an upper floor

Abramovic and participant, "The Artist Is Present"

"The Artist Is Present"

Abramovic

Abramovic and participant

Spectators at "The Artist Is Present," and the entryway (the white line on the floor served as a visual cordon)

Tim Burton balloon sculpture and patrons, first floor, MoMa

Woman sketching Abramovic's "The Artist Is Present"

Participatory art: a museum attendee lying on "Green Dragon Lying"

No comments:

Post a Comment