Now, 10 years later, we're 40 years out from Stonewall, many of the things we mulled over, that C and I and others have discussed for so long, have continued apace. In 2003, the Supreme Court, in its Lawrence v. Texas ruling, struck down all laws criminalizing same sexual activity, dealing a death blow to what underpinned a wide array of anti-gay laws across the country. In addition to civil protections at the state level, 6 states--Massachusetts, Connecticut, Iowa, New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont--will now permit same-sex marriage, New York and the District of Columbia will or aim to recognize same-sex marriages conducted in other states, while a few others including New Jersey, have civil unions. HIV/AIDS treatments have improved to the point that most PWAs can live full and active lives. Today not only have a wide array of people have elected to live openly as LGBTQs, but now people come out at even younger ages and are constantly reshaping what it means to be an out LGBTQ person. Many same-sex and transgender couples are raising children all over the country, and gay families can be found in every part of the United States. Alongside this, key elements and aspects of LGBTQ life have not only entered but are reshaping the public discourse. There are even a 24-hour LGBTQ cable TV channel, Logo, and countless online venues by and about LGBTQ people, and while gay stereotypes persist, they are now counterbalanced, to a great degree, by realistic depictions of LGBTQ people, in all our diversity, in the media. In fact, in 2009, many of the right-wing's anti-gay bludgeons have been blunted; ideas drawn from the pioneering erait's nothing to find LGBTQ courses even at the smallest colleges and universities, and the gay-marriage scare no longer holds the sway it did, despite the success of Prop 8. LGBTQ movements are now global; while Western LGBTQ discourses and ways of living have spread across the globe, distinctive local approaches to equality for LGBTQ people and attempts to end homophobic and transphobic discrimination have also arisen, often in conversation with what has come from outside.

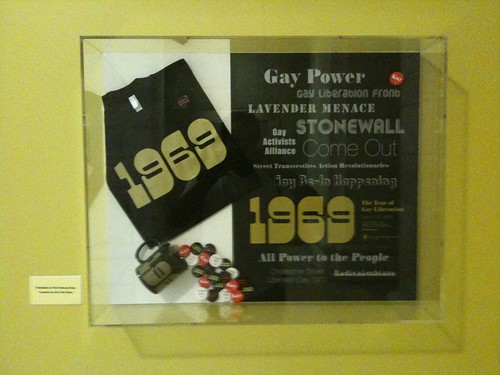

Exhibition sign, "1969: The Year of Gay Liberation," at the New York Public Library Schwartzman Research Branch, NYC

Yet many challenges remain. At the federal level with regard to civil and equal rights, we could from some perspectives still be in 1969. Despite the election of a new-generation Democratic president, Barack Obama, who received overwhelming support from LGBTQ people, we not only have STILL the abomination known the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), signed by our last Democratic president, Bill Clinton, as federal law, but the Obama administration recently defended it with a vigor and viciousness (comparing LGBTQs to pedophiles and incest participants) that would have made even Ronald Reagan blanch. We still have the dreadful, failed Don't Ask Don't Tell (DADT) policy, enacted by Clinton, on the books, and while Obama pens mash notes to military personnel whose lives and careers continue to be destroyed by DADT, he refuses to take executive action or use his bully pulpit to repeal it. A number of states still do not have comprehensive civil protections for LGBTQ people, meaning that you can still be denied a job or fired, prevented from renting an apartment, or even lose your children, if you are thought to be gay. In 2009. The Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), still has yet to be passed by the Democratic-controlled Congress, and Obama, when that happens, has said he will sign it. (Who knows either way?) At the federal level, we still get a lot of window-dressing and scraps, and are expected not to ask for much and be glad for the little we get. No thanks!

(A national march for full equal rights for LGBTQ people is being planned for October 11, 2009, in DC. Will you participate?)

In addition, HIV/AIDS, while now even more manageable than in 1999, continue to disproportionately impact LGBTQs of color, especially black men, and effective prevention efforts have reached a roadblock in the US. Many high-profile LGBTQs have come out, including some very noteworthy people of color, yet a great many continue to remain in the closet and a discourse in defense of the closet or invisibility, as a new form of identity/identification, has now arisen in backlash to outness and public visibility. As I wrote some months ago, verbal and physical attacks on LGBTQ youth, and people in general, have risen in the last few years, and although we have federal hate crime legislation, the problem of bullying of gay youth and police indifference to LGBTQ attacks continues. The emphasis on marriage equality has to some degree overshadowed the broader issue of full, equal civil rights and protections.

One issue that perhaps is of less concern to some but always strikes me is the fragmentation and atomization of LGBTQs that has occurred with our mainstreaming; alongside this I would identify the privatization and corporatization of LGBTQ life, an aspect of the creeping neoliberalization of this society that has been underway for decades. In addition, the mainstream LGBTQ leadership and many major LGBTQ organizations remain too white and too focused on upper-middle-class concerns.

I mourn the loss of gay bookstores, gay bars, gay and lesbian and trans and queer institutions; part of this is nostalgia, but part of this is also a recognition that as far as we've gotten, we still need some of these institutions, perhaps more than we realize. To give just one example, once upon a time I knew I could find the poetry books of queer colleagues at A Different Light (where I first met poet Emanuel Xavier), at Private Visions (where acclaimed artist Glenn Ligon discovered a cache of photographs that served as the basis for several art projects), at the Oscar Wilde Bookshop (where I never met with particularly friendly service, but more than once found books I was seeking. Just last week, I went to five different bookstores in New York City, and not a single one had any the books of a handful of queer poets I know; I felt like I did back in the late 1980s, when I would go to the huge Waterstone's on Newbury Street and press them to order books by LGBTQ writers that I knew were on the bookshelf just around the corner at the Glad Day Bookshop on Boylston, where I worked, just so that they'd be more widely available. This is only one example, but I would ask how far Hollywood has come, for example, and whether we can't see the necessity of queer film festivals, queer-themed and focused theaters, LGBTQ-friendly schools, hospitals, and so on. I'm not arguing for segregation or separation, but wondering what we lose when we surrender what we've created and fail to be vigilant.

Finally I would ask, in echo of the gay men and women I came to know when I first came out, in the mid-1980s, people who were forgers and products of the Gay Liberation ethos born out of Stonewall, we enter and become part of the mainstream, but at what cost? What ultimately do we achieve and how does this affect the communities that we've built and developed? Is there a place for those achievements along the way, or do they enter either the museum or the halls of oblivion?

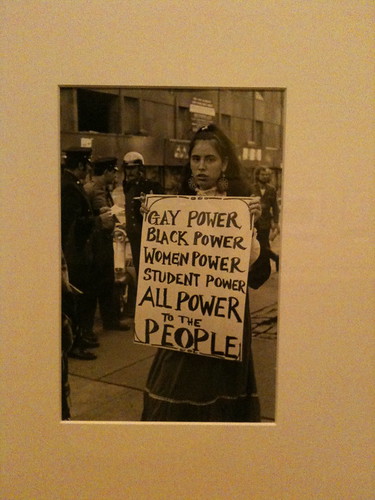

Protestor at Weinstein Hall demonstration for the rights of gay people on the NYU campus, 1970 (Photograph by Diana Davies, Diana Davies Papers), NY Public Library Schwartzman Research Branch, "1969: The Year of Gay Liberation" exhibit

But things will continue to improve, I'm sure. It's amazing to think that the surviving original participants in the Stonewall Riots, and LGBTQ people of their generation, are in their 60s and 70s, while a new generation of LGBTQ people emerges into a very different world made possible, to a tremendous degree, by the events that proceeded and occurred during the Stonewall era, the subsequent push for gay liberation and equality, and the battles in the 1980s to defeat the HIV/AIDS pandemic and extend the gains of the 1970s. For those of us in our 40s and early 50s who have survived the terrible years of the pandemic (and I've written on here before about how it seemed, at a certain point during the late 1980s and early 1990s, that half the gay men I knew from those years were wiped out), today's changes may be striking--gay marriage in Iowa before New York!--and yet at the same time feel inevitable; society was already changing despite the several waves of right-wing backlashes that we witnessed under Reagan-Bush I and Bush II. Where we are now is to a result of the hard and sustained work of liberation and equality, not just for LGBTQ people, but for black people, women, the poor, and all people in the society, that began long before but took concrete, revolutionary form among LGBTQs at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in 1969.

Many changes remain, but we are a lot further along that we were in 1969, when I was 4, or 1979, when I was a teenager, or 1989, shortly after I'd graduated from college. I'm looking forward to seeing where we're going to be 5 and 10 years down the road!

Gay Liberation exhibit poster, NYPL

No comments:

Post a Comment