The news on the unemployment front, like a great deal of what we read and see on TV, has been growing grimmer by the day, and the social conditions behind it are certainly grimmer still. Several people I know well, friends and relatives, have lost their jobs, and others are struggling to make ends meet. Alongside the weak job market, other signs of the economy's sickness are evident everywhere: plummeting home values and rising foreclosures; the appearance of Bushvilles; the collapse of the commercial real estate market; personal bankruptcies resulting from people's inability to pay debts; and on and on. These are only a portion of of the social crisis the country faces, and conditions are as bad or worse overseas. We're officially at 8.9% unemployment, though the reality is probably far worse, which is the worst things have been since the recessionary period around 1983. That was the year I graduated from high school, and one of the reasons I'm able to look back on that period without nostalgia is because, despite my fond memories of particular aspects of being 17 and 18 years old, my perception of the national situation was clear-eyed. In case you don't recall, in 1983 the ur-right winger, Ronald Reagan, was in office; a claque of extreme conservatives were frothing in their new government positions; the Cold War still raged; the AIDS pandemic was steadily increasing, with little attention for the federal government; the crack epidemic was picking up steam, and the concomitant drug war and buildup of the penal system were underway; the US was meddling in a war in Iraq (against Iran, no less, while secretly funneling money from Iran to right-wingers in Central America); and on and on. While I, though penniless and the child of a working-class background, was heading off to college and what I hoped would be a decent future, I was quite aware that things were terrible for others. The lack of jobs, particular for the poor and working-class, for black people, for Latinos, for undereducated whites, was a pressing national concern, which the GOP exploited brilliantly. It would be 10 more years and another recession (along with a young and conservative Democratic president) before the country really turned around. I hope it does not take that long this time, though the underlying conditions do appear to be worse than they were in 1983, or 1993.

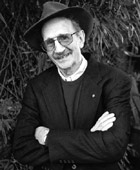

The news on the unemployment front, like a great deal of what we read and see on TV, has been growing grimmer by the day, and the social conditions behind it are certainly grimmer still. Several people I know well, friends and relatives, have lost their jobs, and others are struggling to make ends meet. Alongside the weak job market, other signs of the economy's sickness are evident everywhere: plummeting home values and rising foreclosures; the appearance of Bushvilles; the collapse of the commercial real estate market; personal bankruptcies resulting from people's inability to pay debts; and on and on. These are only a portion of of the social crisis the country faces, and conditions are as bad or worse overseas. We're officially at 8.9% unemployment, though the reality is probably far worse, which is the worst things have been since the recessionary period around 1983. That was the year I graduated from high school, and one of the reasons I'm able to look back on that period without nostalgia is because, despite my fond memories of particular aspects of being 17 and 18 years old, my perception of the national situation was clear-eyed. In case you don't recall, in 1983 the ur-right winger, Ronald Reagan, was in office; a claque of extreme conservatives were frothing in their new government positions; the Cold War still raged; the AIDS pandemic was steadily increasing, with little attention for the federal government; the crack epidemic was picking up steam, and the concomitant drug war and buildup of the penal system were underway; the US was meddling in a war in Iraq (against Iran, no less, while secretly funneling money from Iran to right-wingers in Central America); and on and on. While I, though penniless and the child of a working-class background, was heading off to college and what I hoped would be a decent future, I was quite aware that things were terrible for others. The lack of jobs, particular for the poor and working-class, for black people, for Latinos, for undereducated whites, was a pressing national concern, which the GOP exploited brilliantly. It would be 10 more years and another recession (along with a young and conservative Democratic president) before the country really turned around. I hope it does not take that long this time, though the underlying conditions do appear to be worse than they were in 1983, or 1993.That said, I've been thinking about poems dealing with work and labor, and in particular poems I have not posted before (thus excluding "Those Winter Sundays") and one came immediately to mind: Philip Levine's "What Work Is." I first came across this poem when I heard Levine read it on public radio; I believe this was after the eponymous collection had won the National Book Award. That would have been back in 1991 or 1992. I remember tearing up when he got to the end of the poem, I was so verklempt, and I sought out his work, which I was utterly unfamiliar with, right away. About five years later, when I was in graduate school, Philip Levine was teaching a poetry workshop that I was unable to take, but he would sometimes sit in the graduate poetics class I audited (which did not, unfortunately, cover his work), something I've never seen another "famous" poet do (he knew the professor, but even still, it rarely happens), and I kept saying that I would introduce myself and praise his work, but I never did muster the courage. I got to hear him read his work live around that time, though, and when I got his autograph in my copy of What Work Is, I offered my little valentine. Here's his poem, which could have been written last week, about what occurred last week.

What Work Is

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is--if you're

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers,

and of course it's someone else's brother,

narrower across the shoulders than

yours but with the same sad slouch, the grin

that does not hide the stubbornness,

the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours wasted waiting,

to the knowledge that somewhere ahead

a man is waiting who will say, "No,

we're not hiring today," for any

reason he wants. You love your brother,

now suddenly you can hardly stand

the love flooding you for your brother,

who's not beside you or behind or

ahead because he's home trying to

sleep off a miserable night shift

at Cadillac so he can get up

before noon to study his German.

Works eight hours a night so he can sing

Wagner, the opera you hate most,

the worst music ever invented.

How long has it been since you told him

you loved him, held his wide shoulders,

opened your eyes wide and said those words,

and maybe kissed his cheek? You've never

done something so simple, so obvious,

not because you're too young or too dumb,

not because you're jealous or even mean

or incapable of crying in

the presence of another man, no,

just because you don't know what work is.

Copyright © from Philip Levine, What Work Is, New York: Knopf, 1992.

No comments:

Post a Comment