I've rhapsodized about the Met before on here, so I'll spare readers that bit, but I will say that if you are visiting New York and are at all disposed to art and you have some spare time and you don't have a particular show in mind, the Met is the museum to visit. (I would place the Brooklyn Museum second in this regard, plus you get the added option of taking the subway train to Brooklyn.) Whatever your area of aesthetic interest, the Met probably has something to sate it, or at the very least, whet it. Optimally you would have several weeks to explore the museum section by section, savoring its troves, but that's rarely possible, so I suggest picking an area--the arts of Japan, say, or the Temple of Dendur--and then just devote a few hours to it, viewing what the Met has to offer. It's never time wasted. (Just remember that the "suggested" fee is now $20. Keeping up with the MoMas, you know.)

But back to the Afghanistan exhibit, I found it a great choice. Most of the pieces had been unearthed or preserved up until the period of the Russian invasion, in 1979, which led to untold horrors, not the least the US's arming of the mujihadeen, including someone named Osama bin Laden, almost continuous instability in many parts of the country, and the Taliban regime, whom the US is still ostensibly engaged in a war against. Another effect of this chain of events was widescale destruction of Afghanistan's artistic and cultural patrimony. Perhaps one of the most notorious moments occurred in March 2001, when the Taliban, in an attempt to prevent idolatry, blew up the giant 6th century, sandstone Buddhas of Bamyan, in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan.

To prevent looting and the complete destruction of the country's ancient treasures, members of the Kabul Museum's staff secreted them away in vaults in the Central Bank area of the presidential palace. It wasn't until 2004 that many of these artifacts, dating from 2200 BCE to the 2nd Century AD, when regions of northern Afghanistan, such as the area around Mazar-i-Sharif, and known as Bactria among ancient writers, represented a central crossroads along the centuries-long Silk Road trade, were exhumed and again available for viewing not only by Afghans, but by the wider world.

As the catalogue and exhibit literature suggests, the art shows contact with of a variety of traditions, including Greece, Persia, Mesopotamia, India, China, and the Eurasian steppes. Some of the pieces seemed redolent of certain traditions more so than others; in the case of carved ivory panels that would have been part of a throne or chair for a dignitary, the imagery, stylizations, and iconography reminded me strongly of eastern Indian art. Other works, such as figurines, looked like similar work on display in the Greek and Roman galleries. There were even some signet rings, found in nomadic tombs in Tillya Tepe, on the Eurasian steppes, which could easily have been fashioned during the most psychadelic periods of the late 1960s and early 1970s. In fact, the art on display came from four sites, according to the Met's literature:

The intricacy of detail and extraordinary craftspersonship of the pieces on display impressed me, and though it was cursory at best, I felt like I gained some insight, through these artifacts and the elaborate contexts that museum attempted to delineate through the various wall plaques and related literature, into the lifeworlds of the people who originally made and made use of them.

the Bronze Age site of Tepe Fullol; the Greco-Bactrian city of Aï Khanum, founded by the successors of Alexander the Great, who conquered the region in the fourth century B.C.; the major trading settlement of Begram, which flourished at the heart of the Silk Road in the first and second centuries A.D.; and the roughly contemporary necropolis of Tillya Tepe, where a nomadic chieftain and members of his household were buried with thousands of stunning gold objects and ornaments, many inlaid with turquoise and other semiprecious stones.

Their functionality and centrality to various daily experiences, rituals, spiritual and cultural practices, to the life of the communities in which they were created, to particular and quite distant political and social economies that in some ways still reflect our own, became apparent as I walked through the show and viewed and read. The heroism, which to put it another way might be the determination, of the museum staff, to preserve these vital links to Afghanistan's--and our human--past, also impressed me deeply, and made me think for a bit about what we value in this society, what we have valued, what we leave for those to come, whether we call it art or have no name for it at all, who has access to it and what its roles and functions are.

I bore this with me as we left this particular exhibit and viewed a few other things in the museum, including the Roxy Paine sculpture, Maelstrom, a gigantic (130-foot-long by 45-foot-wide) stainless steel "dendrite," in the Cantor Roof Garden; the new American Wing of the Museum, since May 19 comprising the bright, airy Engelhard Court and several floors of period rooms; some works in the Oceanic art collection; and a smallish exhibit (or room) I can't find online, featuring some landmarks of 20th century design. We spent a good amount of time in the Engelhard Court, the centerpiece of the new American Wing, which First Lady Michelle Obama helped to inaugurate back in May; an exhibit of sculptures by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whom I always associate with Boston and the Common, and with Robert Lowell (because of his famous poem "For the Union Dead"), graced that space. It felt a bit haphazard, scattered, though some of the pieces, such as the "Diana" which had once stood atop the old Madison Square Garden before its leveling, matched the vastness and grandeur of the room. I did not visit more than a few of the period rooms, something I must return there to do soon, and am looking forward to the completion of the painting galleries, which will not open, if I read the note correctly, for several more years. Still, the Engelhard Court would probably be a great place to pause and reflect, perhaps even have a cup of coffee, and reflect upon what you've seen, before heading to another part of the museum.

And as always, photos:

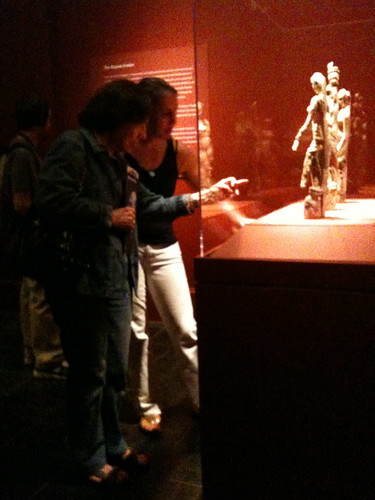

People looking at some of the sculptures, Hidden Treasures of Aghanistan exhibit

Statuettes and figurines, Afghan art exhibit

Busts and vases, Afghan art exhibit

Salvador Dalí's "Crucifixion," 1954

David Hockney screen, in the design show

Charles Demuth's "The Figure Five in Gold," 1928

Photographers in the Engelhard Court

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Statue of Diana, Engelhard Court

South Sea Islander Fishing Chart, Arts of Oceania collection

Roxy Paine's Maelstrom

Maelstrom

Photographers in the Engelhard Court

The Engelhard Court's south end, featuring the installed façade of Martin E. Thompson's Branch Bank of the United States (1822-24), originally located at 15 1/2 Wall Street in New York City

No comments:

Post a Comment