Instead of posting to the blog, I've been reading; writing my novel and short stories; reading; reading grad student work, since that's a year-round responsibility; reading; mourning; reading; trying to write an essay in French; reading; writing letters and emails to politicians and donating when possible to support progressives; reading; preparing for conferences later this year and early next; reading; listening to the radio and watching far too much TV, including almost anything that happens to be broadcast by Bravo; reading; watching Netflix films; reading; going to the movies and wondering how Hollywood stays in business; reading; hitting the gym regularly; reading; hanging out with a few friends and seeing others off as they move across the country; reading; working on other literary projects; reading; dreaming of new ones; reading; reading blogs, magazines, journals, newspapers, especially if I did not have an opportunity to read them during the past academic year; reading; tweeting (as you now know) and reading others' Twitter feeds; reading; , not following Facebook all that much; and doing all the other things that I do when I'm home in New Jersey.

As I noted on my Twitter feed, one of the books I finished recently was Benjamin Moser's biography of Brazilian 20th century great Clarice Lispector, Why This World (Oxford, 2009). In fact, as soon as Reggie H. (naturally) mentioned that the book was out, I ran to 2 different bookstores in NYC (my favorite in Jersey City having closed this past spring), and one, the independent Three Lives in Greenwich Village, was able to get it for me in a day. Moser's true skill in the book, beyond his thoroughness, his assured narration, and his infectious enthusiasm, sometimes to the point of hagiography and hyperbole, is to trace out the autobiographical skeleton and philosophical underpinnings of Lispector's work, revealing how so many aspects of her life, beginning with her Jewishness, and ranging from her family's hair-breadth escape from the pogroms in Ukraine, to the horrific suffering of her mother during that period, to her childhood in the exciting but still backwater northeastern capital of Recife, all helped to mold Lispector's life trajectory in singular ways that distinguished her, as a creative person as well as a public figure, from all of her Brazilian peers and gave her work its indelible, and indelibly strange and compelling stamp. One effect of the book was to make me want to return to all the Lispector books I'd read before, like The Passion of G. H. and Stream of Life (Agua Víva), two of her greatest, as well as her masterpiece, The Hour of the Star (whose famous English translation, by Giovanni Pontiero the scholars César Braga-Pinto and Ben Sifuentes-Jaureguí told me, is quite faulty, as it leaves out an entire paragraph and mistranslates others), and to read the ones I'd never gotten to, like The Foreign Legion, or The Chandelier. It also expanded my understanding, via its recourse to biography and historiography, of all of these works, in ways I hadn't imagined. Thus with The Passion of G. H., what is playing out in this book in part is Lispector's coming to terms with a capacity for self-understanding so brutal, so obliterating, that its materialization as the book's fictional plot in a sense must result in the horrific scene (which I will not give away) that continues to shock and surprise readers. Moser suggests that Lispector had reached not only an aesthetic, but a philosophical limit with this book, and goes on to show how what followed takes up another major strand that was present in her earliest writing. I should add that there are many fascinating biographical nuggets in the book, such as that Lispector, of all people, once translated, quite lackadaisically, Ann Rice's Interview with a Vampire into Portuguese; that an American poet became so enamored of her that he threatened suicide if he couldn't be with her (he couldn't); and that she was once invited to a paranormalist conference in Colombia based primarily on the wealthy organizer's impression that she was a "witch," by which I mean in the supernatural sense. More than anything, though, Moser's biography helped me to appreciate Lispector's achievements that much more, providing a much more detailed context in which her work appeared, and a deeper sense of its impact on her national literature as well as outside Brazil. The Hour of the Star, in its flawed English version, sits amidst the stack of books I plan to get through by the end of December, but I also am going to try, if I can, to approach the Portuguese to see exactly what it is I--and most of her English-language readers--have been missing.

As I noted on my Twitter feed, one of the books I finished recently was Benjamin Moser's biography of Brazilian 20th century great Clarice Lispector, Why This World (Oxford, 2009). In fact, as soon as Reggie H. (naturally) mentioned that the book was out, I ran to 2 different bookstores in NYC (my favorite in Jersey City having closed this past spring), and one, the independent Three Lives in Greenwich Village, was able to get it for me in a day. Moser's true skill in the book, beyond his thoroughness, his assured narration, and his infectious enthusiasm, sometimes to the point of hagiography and hyperbole, is to trace out the autobiographical skeleton and philosophical underpinnings of Lispector's work, revealing how so many aspects of her life, beginning with her Jewishness, and ranging from her family's hair-breadth escape from the pogroms in Ukraine, to the horrific suffering of her mother during that period, to her childhood in the exciting but still backwater northeastern capital of Recife, all helped to mold Lispector's life trajectory in singular ways that distinguished her, as a creative person as well as a public figure, from all of her Brazilian peers and gave her work its indelible, and indelibly strange and compelling stamp. One effect of the book was to make me want to return to all the Lispector books I'd read before, like The Passion of G. H. and Stream of Life (Agua Víva), two of her greatest, as well as her masterpiece, The Hour of the Star (whose famous English translation, by Giovanni Pontiero the scholars César Braga-Pinto and Ben Sifuentes-Jaureguí told me, is quite faulty, as it leaves out an entire paragraph and mistranslates others), and to read the ones I'd never gotten to, like The Foreign Legion, or The Chandelier. It also expanded my understanding, via its recourse to biography and historiography, of all of these works, in ways I hadn't imagined. Thus with The Passion of G. H., what is playing out in this book in part is Lispector's coming to terms with a capacity for self-understanding so brutal, so obliterating, that its materialization as the book's fictional plot in a sense must result in the horrific scene (which I will not give away) that continues to shock and surprise readers. Moser suggests that Lispector had reached not only an aesthetic, but a philosophical limit with this book, and goes on to show how what followed takes up another major strand that was present in her earliest writing. I should add that there are many fascinating biographical nuggets in the book, such as that Lispector, of all people, once translated, quite lackadaisically, Ann Rice's Interview with a Vampire into Portuguese; that an American poet became so enamored of her that he threatened suicide if he couldn't be with her (he couldn't); and that she was once invited to a paranormalist conference in Colombia based primarily on the wealthy organizer's impression that she was a "witch," by which I mean in the supernatural sense. More than anything, though, Moser's biography helped me to appreciate Lispector's achievements that much more, providing a much more detailed context in which her work appeared, and a deeper sense of its impact on her national literature as well as outside Brazil. The Hour of the Star, in its flawed English version, sits amidst the stack of books I plan to get through by the end of December, but I also am going to try, if I can, to approach the Portuguese to see exactly what it is I--and most of her English-language readers--have been missing. Speaking of movies, and in particular movies about vampires, which are still all the rage (cf. Monster Theory), one I recommend, is the Swedish horror film Let the Right One In (2008), directed by Tomas Alfredsson. Anyone who watches the enthralling, disturbing, and sometimes outright farcical True Blood (or has read Stoker, Rice, and others), knows the basics of vampire lore, such as the threat from the sun, the necessity of being invited into human beings' homes, and the overwhelming need for blood, and Alfredson hews to them even as he creates something quite fresh, a revenge tale of sorts involving two children, one a vampire and one not, in an utterly bleak and yet beautiful Stockholm. The story centers around an androgynous, taciturn and almost frighteningly pale little boy, Oskar (Kare Hedebrand), whose parents are divorced and who's the victim of continuous bullying by a group of schoolyard thugs. Raised by his single mother in an ice-laden apartment complex which appears to be fairly devoid of people--really, the setting alone was already scaring me--he encounters a raven-haired little girl, Eli (Lena Leandersson), who turns up one day, amidst the frigid weather, without so much as a coat. Eventually he learns why Eli doesn't appear to be bothered by the cold, and why he doesn't see her during the day; he also learns that he's falling in love with her, despite some bloodcurdling aspects of who she truly is. The acting in the film is almost perfect, it manages to invoke tenderness without sentimentality, and though it become quite clear how the plot is going to unfold, at least up to the end, which Alfredson sets up in very skillful fashion early on, the movie still provides a good deal of immersion into vampirism, and real horror, including the requisite bloodletting.

Speaking of movies, and in particular movies about vampires, which are still all the rage (cf. Monster Theory), one I recommend, is the Swedish horror film Let the Right One In (2008), directed by Tomas Alfredsson. Anyone who watches the enthralling, disturbing, and sometimes outright farcical True Blood (or has read Stoker, Rice, and others), knows the basics of vampire lore, such as the threat from the sun, the necessity of being invited into human beings' homes, and the overwhelming need for blood, and Alfredson hews to them even as he creates something quite fresh, a revenge tale of sorts involving two children, one a vampire and one not, in an utterly bleak and yet beautiful Stockholm. The story centers around an androgynous, taciturn and almost frighteningly pale little boy, Oskar (Kare Hedebrand), whose parents are divorced and who's the victim of continuous bullying by a group of schoolyard thugs. Raised by his single mother in an ice-laden apartment complex which appears to be fairly devoid of people--really, the setting alone was already scaring me--he encounters a raven-haired little girl, Eli (Lena Leandersson), who turns up one day, amidst the frigid weather, without so much as a coat. Eventually he learns why Eli doesn't appear to be bothered by the cold, and why he doesn't see her during the day; he also learns that he's falling in love with her, despite some bloodcurdling aspects of who she truly is. The acting in the film is almost perfect, it manages to invoke tenderness without sentimentality, and though it become quite clear how the plot is going to unfold, at least up to the end, which Alfredson sets up in very skillful fashion early on, the movie still provides a good deal of immersion into vampirism, and real horror, including the requisite bloodletting.***

One thing I've been trying to do is not let the increasingly crazed political situation in the country, particularly swirling around health care reform, send my blood pressure into the outer stratosphere. The GOP bringing the crazy isn't surprising; they gave us more than enough of a preview last year, and have, as the consensus historian Richard Hofstadter pointed out before I was born, the Republican Party has long been a repository for extreme nuttiness, though I think things really took a turn for the worst under 1) Reagan's presidency, when illogic was actively embraced and empowered, and 2) when Bill Clinton won in 1992. The right wing, including its Congressional annex, became totally unhinged at that point, which culminated in the attempted impeachment of Clinton in the late 1990s, despite his having governed as a competent, moderate Republican for nearly half a dozen years, and the 2000 coup that installed George W. Bush. (Yes, that sounds nutty too, but the 2000 election, if you think about it, was hardly legitimate.)

Part of the problem has been what I view as a lack of leadership and forcefulness, and an almost reflexive accommodationism, from President Barack Obama. Now I did say that I would be publishing some political thoughts back around the time of his 100th day in office (an arbitrary guidepost that the legacy media turned into a referendum moment of sorts), which I glibly called "100 Days of Obamatude," but my rising disillusionment with his tenure thus far has reached the point--perhaps disillusionment isn't the right word, and disappointment is more apt--where I haven't been able to muster the energy to commit the critique here. I do still support him, and do not regret that I voted for him. And yes, there were omens of what we've seen from his time in the Senate, one of the most outrageous being his total flipflop last year on the FISA bill and telecom immunity; his cravenness on this issue was about as huge a flag as there was. Others pointed, in a kindly but firm manner, to his narcissism, blinding self-regard and apparent entitlement (though what major politician doesn't possess either), his lack of experience and thin resumé, and his congenital desire to compromise. None of these things are and should never be dealbreakers for a president, and in light of who he was running against--and I don't just mean the loony GOP ticket--he looked then and continues to have been the best choice. On a symbolic level, he has been decent to very good so far, and some of his efforts, like his shepherding the flawed but necessary stimulus bill through Congress, his nomination of Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, his lifting of some Bush-era extremist regulations concerning reproductive rights, and his championing of the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Bill, have been exemplary. However, in so many other areas, the rhetoric and actions have been equivocal to dismal enough to provoke deep cynicism, in addition to dismay, disgust, and worse. I won't enumerate them all now (his economic approach and the ongoing sub-dom relationship with Wall Street; the continuation of the Bush torture regime; the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and his dealings with the military leadership; the disquieting indifference towards LGBTQ equality and rights; etc.), but the health care reform issue and the consequent battle provide a good example.

When he was campaigning over the last two years, Senator Barack Obama outlined many elements of what he foresaw as necessary to ensure real health care reform, a fact that is probably evident to anyone who isn't rich, is over 35, and has to deal with our current health care system. Two of Obama's rivals for the nomination, John Edwards (who despite a plethora of ideas thankfully did not get that far) and Hillary Clinton, proposed more sweeping and progressive health care reform plans, and when he was elected, Obama appeared set--and suggested, in his public comments--that he was going to adopt most of the better features of the Edwards and Clinton plans, and marshal them through Congress, thus transforming, in Rooseveltian fashion, the contemporary health care landscape in the United States. As the battle--and it was always going to be a battle, because the GOP, from before November 4, 2008, demonstrated its deep and abiding opposition to an Obama presidency, and has done nothing to change that--has unfolded, Obama, along with key elements of the Democrat party, has repeatedly said one thing and done another, misled and outright insulted his strongest supporters, cowered and gone oddly silent at times in the face of vicious GOP attacks and very dangerous, destructive lies, and shown very little passion or consistency on what is literally a life-and-death issue.

One of the key things President Obama promised was "transparency" surrounding the health care push, but we've since come to learn that in fact we've gotten anything but. Instead of the discussions being broadcast on CSPAN, we've learned that key White House officials may (or may not, though it's likely they did) negotiate in advance both with Big Pharma and the insurance companies to give them a great deal of what they wanted, in effect suffocating real, transformative reform before it was ever really possible. The White House also keeps involving perdurable milquetoast and former Senator Tom Daschle, a man who while Senator Majority Leader never missed an opportunity to let the GOP roll right over him; Daschle was supposed to be the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and thus to help "fix" this whole health care "reform" effort, since he has spent his post-Senate career joining his wife in shilling for a host of health care industry clients, but he failed, unlike the masses of we little people of whom Leona Helmsley once so contemptuously spoke, to pay his taxes, so his official stint in the Obama administration was kiboshed. He nevertheless continues to keep a finger in the mix--those powerful, wealthy clients, you know--and so we've gotten this horrendous, ridiculous notion of health care co-ops, which none of their proponents can lucidly explain, in place of the already watered-down government, or "public" option, which itself is a watered-down version of what would truly transform US health care, slash costs, and make quite a few insurance and pharmaceutical execs and shareholders very unhappy: a universal, single-payer system. Obama continues to finagle with Daschle, and the "Gang of Six" in the Senate, led by notorious conservadem Max Baucus, and will still have to deal with the rest of the Blue Dogs in both the Senate and House, as well as ideological Mr. Hydes like Arlen Spector (support Joe Sestak and do Pennsylvania and the country a favor!) and Joe Lieberman, who are probably salivating at the chance to sabotage whatever the Democrats produce, so who knows what will ultimately emerge and be labeled "health care reform." It's clear that without a public option, if purchasing a health care package is mandated, the main beneficiaries, under George Bush and the Republican Congress's boondoggle, will be the insurance industry and Big Pharma, again. But we're being conditioned, badly of course, to be ready to accept whatever does appear, which Obama will sign and thus declare as a victory. Half-assed is now supposed to cut it. And we're supposed to say, as we've had to say again and again with this administration (and as was the case, I recall, under Clinton, when he was not turning into an outright Republican on social or economic policy), well, it was better than nothing, which is, admitted, something....

It certainly doesn't help that we have such a hapless, duplicitous, corporate-muzzled legacy media, but I already knew this. I've railed about them more than once on this blog. The vast majority of print and telemedia journalists and the accompanying punditocracy were going to be worthless when it came to the health care reform issue, just as they'd been worthless, to a perilous extent, throughout the 8 years of George W. Bush--and Clinton's two terms, where the leading paper of record, the New York Times, to give just one execrable example, distinguished itself by pushing the Whitewater scandal relentlessly until it was finally debunked and Bill and Hillary Clinton were exonerated, by courts of law no less, of wrongdoing, yet the Times never saw fit to apologize for its highly damaging behavior. We are now near the end of August, yet one could search high and low for a clear, extended discussion, on TV or in the major papers, of what the current health care issues are, why the US spends so much more than any other industrialized country and what the sources of these exorbitant costs are, what the prospective Congressional plans would really look like and how they would play out economically, what various real stakeholders (from patients to doctors to insurance and pharmaceutical executives, etc.) would stand to gain and lose, and what the projected effects, not just on the health care system itself, but on US society in general, would be. Perhaps the media didn't do this when Social Security or Medicare and Medicaid were being discussed either, so maybe this is beyond their pay grade or ken, but in the absence of the Democratic Party, major Democratic Congressional officials, and the President doing this in a sustained fashion--and thus helping to counter the sheer derangement being catapulted, for obvious reasons, by the insurance and Big Pharma lobbies and by the likes of Sarah Palin and a good deal of the GOP--having the legacy media just do its job would have very helpful and productive, whatever the outcome of the health care reform push might be.

So, as I said, I try not to let it or them get to me, whether it's Andrea Bernstein on WNYC's Brian Lehrer Show expressing relief that reporter and author T.R. Reid was not a "leftwing nut" and failing to ask basic questions about economic baselines and costs of Reid, whose new book, The Healing of America: A Global Quest for Better, Cheaper, and Fairer Health Care, on his experiences with universal health care systems in the world's other advanced democracies sounds fascinating, or Chris Matthews parroting right-wing talking points one minute while bemoaning right-wing behavior the next, or the President and his administration negotiating against themselves, either because they want the bill to fail or be torn apart and fairly worthless if it does pass, they're somehow cowed by the GOP and completely beholden to the industries they're supposed to be challenging, or they're just too in their salad days--or, and I hope this isn't the case, too incompetent--to grasp how to deal with the opposition. Of course there could be other reasons why the situation is unfolding the way it is, so pardon any ascriptions of bad faith to the President (if not to people like Rahm Emanuel, a corporatist if there ever was one), but it's frustrating to witness things occurring--ravel, really--as they are, and to realize that I, nor anyone else really without power or access, has any voice, no matter how insistent we are.

***

One of the things I've been doing is making bread. In addition to saving money every week, because this homemade bread is far cheaper than store-bought or even farmer's market-bought bread, and does last quite a while (sometimes up to 2 weeks without getting hard or moldy), the breadmaking is quite therapeutic. Each loaf has been an improvement on what's come before, it's fairly easy to do and hard to screw up even with a bit of experimentation, and it's so satisfying and delicious when it's done. As I mentioned, I started making it in Chicago, after C had pioneered it in NJ, and since then I haven't slowed down. So here are four different types of some of the breads I've been making and we've been enjoying.

First, I want to highlight the Irish soda bread I made based on a recipe that my former undergraduate student, the very brilliant Miriam*, who currently is on the high seas but does manage to post comments here regularly, sent me some time ago. (Finally, I made it!) I love Irish soda bread, and was particularly fond of the version the Plough & Stars, a longtime Cambridge, Massachusetts bar (is it still there?), used to serve on Sundays, with eggs and Irish sausages, a perfect tonic to sop up a hangover and fortify you for the rest of the day, so I decide to try my hand at making some, and it turned out very well. To Miriam's recipe I added raisins and perhaps more butter than was necessary, so the crust was quite flaky, but it did hold up well whether sliced and covered with marmelade, fried in an egg-in-the-hole style service (particularly delicious), or battered and turned into French toast. The innate sweetness and thickness of the bread made it especially perfect for this purpose. It also kept, first in a simple plastic bag, and then later in the refrigerator, for about 2 1/2 weeks.

An overhead shot of the Irish soda bread. It was particularly delicious with eggs, and as the base for French toast.

The Irish soda bread from the side. Those are raisins lying on the pan.

Back in late June, I made semolina loaves, another favorite from the farmer's market. C had suggested that I just adapt the recipe I regularly used but substitute the semolina instead of the wheat flour, but I thought I should try to find a semolina recipe, and I did, and it was considerably more involved than my usual minimal knead recipe, but the results, visible below, were pretty good, so I do plan to try it again. Like the Irish soda bread but unlike the boules, it doesn't go in a pot, but bakes on a tray, though with a pan of water beneath it, to ensure that it has the space to rise but forms a good crust and achieves a light, puffy texture. I am going to try it again, but perhaps with more of a sourdough flour to see how that turns out, though I'm not so much a fan of sourdough as I am of other doughs. The bread last for about 2 weeks, stayed soft, unlike other semolina loafs we've bought, even from bakeries, and was perfect plain, buttered at breakfast, to make sandwiches, what have you.

My next experiment was making an olive loaf, using the unbleached bread flour, the unbleached white flour (as opposed to the whole wheat or rye flour), and the pastry flour. Olive loaves are one of our favorite purchases at the farmer's market. Since I am boycotting Whole Foods, which I know has delicious, not excessively brined fresh olives, I picked up several different types of fresh, black and dark olives from the local A&P. They were extremely brined, so to prepare them for the olive bread, I made sure they were pitted, washed them 2-3 times, then tasted them to make sure they weren't too salty, then diced them up so that they would be easy to knead into the bread. At the stage when I knead the bread shortly before I bake it, I folded the olive pieces in, and then let the dough rise again for about 30-45 minutes. The result was, if I may say myself, quite successful. The second version I made the other night also worked well, and baked into an almost heart-shaped version, which is easier to cut for sandwiches. The original loaf lasted about 2 weeks, and did not harden or grow moldy, even though not refrigerated.

The olive loaf. I washed the olives three times to remove the brine (and pitted the ones that weren't already pitted).

This is the original white loaf, with pecans, that I've been making a lot. During the winter I tended to make a whole wheat version, and also tried a rye version. (I need to learn how to make pumpernickel.) It's my personal favorite, in part because the nuttiness of the pecans really flavors the bread in a wonderful way that doesn't overpower it. Whether for sandwiches, as an accompaniment to a lunch salad or with dinner, or even to make croutons or bread pudding once it nears the end of its freshness, it's a great option. Without the pecans it would be tasty, but with them, it is simply beyond.

My favorite, the standard pecan loaf.

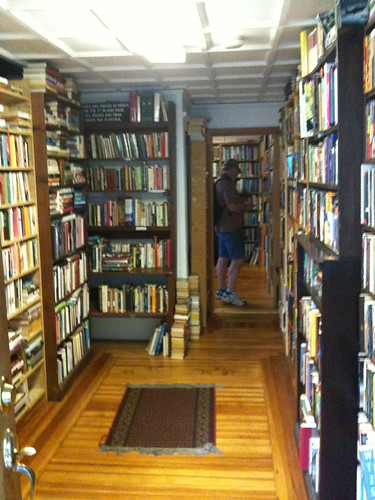

*In an earlier comment section, Miriam noted a great used bookstore on Commercial Street in Provincetown; I did not publish the photo of it, but I snapped a picture, as I often have, as I was entering it, and titled it "My favorite Ptown bookstore" on my Flickr photostream. Why am I not surprised that Miriam would have mentioned it? :-)

No comments:

Post a Comment